.: How the Grinch Stole Star Wars

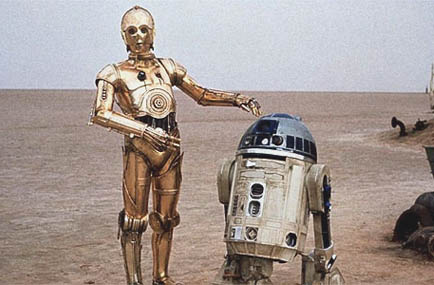

On May 25th, 1977, a film opened in 32 theaters in the United States and changed not only the movie business itself, but the popular culture unto which it was released. Star Wars not only quickly became a pop fad of the summer of '77, it endured as a monumental and historical achievement in cinema, not just as an entertainment piece of great cultural value, but as a "blockbuster" or "popcorn" film, as a special effects extravaganza, as a sci-fi fantasy picture, as a franchise, as a cinematic epic, and as a classic of American film. By the end of the year, it was the most financially successful motion picture of all time, and at the Oscars it saw nominations for Best Picture, Best Director, Best Screenplay and Best Supporting Actor, among an additional seven which it won.

Simply put, Star Wars is one of the most influential films ever made and quite possibly it is the most popular singular film of all time.

When it was re-released in an altered form in 1997, it knocked JERRY MAGUIRE out of the box office and stayed at number one for four weeks in a row, earning an additional $138 million--not bad for a twenty year old film. It currently stands on AFI's Top 100 Films list at number thirteen, beating 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY, PSYCHO, SUNSET BULLEVARD, THE MALTESE FALCON, KING KONG, TAXI DRIVER, and HIGH NOON.

However, nobody has seen this original film theatrically for over twenty-five years, and its most recent dedicated release on home video was a VHS and Laserdisc--in 1995. How could such a travesty of cinema history happen? How could one of the most important and popular films of all time remain essentially lost? It seems George Lucas lost his mind somewhere between 1977 and 1997 and decided that 1977's STAR WARS would be destroyed.

STAR WARS was the first VHS to make a million dollars in rentals when it came out in 1982--although technically, this was not the original version either, for in 1981 the subtitle "Episode IV: A New Hope" was added to the title crawl; but, barring this single, rather insignificant change, it was the same film. STAR WARS and its two sequels, EMPIRE STRIKES BACK and RETURN OF THE JEDI, were not only three of the most popular films in history--until the late 1990's, they all occupied the top ten box office list--but the most impactful, and even in 1987 Mel Brooks had paid tribute to the films in his parody SPACEBALLS.

In 1989, the Library of Congress added a print of STAR WARS to its archive, the National Film Registry, representing a preservation of films with great artistic and cultural value. Printed in a 1993 video boxset release, Lucas wrote a letter to fans, saying "Star Wars was my elaborate fantasy, but its popularity has gone beyond anything ever I had imagined...I hope that you, your children, and your children's children will enjoy experiencing this saga as much as I have."

That same year, Lucasfilm and Fox began discussing the upcoming twentieth anniversary of the original film. "One of the reasons I chose to reissue the films rather than do a convention or one of the other things that was suggested for the twentieth anniversary was at the time we thought about all of this I had a two-year-old son," Lucas would later explain. "And I thought, 'I'm not going to show him the film on video, I'm going to wait and let him see it on the big screen the way it was meant to be, and let him really be overwhelmed by the whole thing.' Lucas remembers in 1997: "This was supposed to be a nice little twentieth anniversary for the fans." Lucas had also long complained about a compromising 1976 shoot, and surmised that perhaps a few special effects could be added or cleaned up, similar to the way Steven Spielberg had done a slightly spiffier CLOSE ENCOUNTERS "Special Edition" in 1980.

"[Fox said], 'we should celebrate the fact that we've been here for twenty years.' I said, 'If you're going to put that much money into reissuing the movie, I want to get it right this time.' " Lucas' main idea was to expand the Mos Eisley space-port sequence and restore a deleted scene with Jabba the Hutt. "The initial scope of it involved just two dozen shots," ILM animator Tom Kennedy says. FX wiz Dennis Muren then suggested that the release offered the opportunity to correct a list of fifteen to twenty shots that had always bothered him. "I suggested to George that we expand the vision and he was open to it," Muren says. "Motion issues, particularly in the space battle scenes, were my concerns. Then Tom Kennedy and the others contributed their own ideas for redoing shots."

The "Special Edition" was slowly growing in scale. Lucas was eager to use new CG technology--he had just announced he was making the prequels, and the Special Edition of STAR WARS was free research and development since Fox was paying the bill. "We called it an experiment in learning new technology," Lucas says, "and hoped that the theatrical release would pay for the work we had done." Many new insertions were decided upon the basis of their usefulness as learning tools--how to do crowd replication, how to handle extreme close-ups on CG characters, etc.

By the time this "Special Edition" was complete in 1997, the original camera negative had been restored, the sound remixed in 5.1 channel surround, many special effects were re-composited digitally, and the film had been enhanced with CGI in approximately 35 shots, and with an additional 30 brand new shots, offering a markedly different viewing experience.

Fox had spent close to $20 million for this enhancement, twice the budget of the original production. Many fans felt nonplussed by most of these additions--Greedo inexplicably shot (and missed, from two feet away) before Han did in order to "soften" Han's character, "kiddie" humor was abound in slapstick CG droids, and even the long-awaited Jabba scene disrupted the pace, gave redundant information, showcased a lacklustre CG model and had Boba Fett posing for the lens.

But, in spite of some mixed opinions about the changes, the real reason for the release was a chance to see STAR WARS on the big screen, and to that end it was a remarkable experience that brought in more money than all but the top six films that year (TITANIC, MEN IN BLACK, LIAR LIAR, THE LOST WORLD, AIR FORCE ONE and AS GOOD AS IT GETS). The public--not just "fanboys"--loved the chance to see the film again on the big screen.

However, most did not realize that Lucas had other plans. This version--a "Special Edition": an enhanced, "nice little twentieth anniversary for the fans" and "an experiment in learning new technology"--would soon enough replace the historical, groundbreaking original, which would never, ever be seen again.

Lucas furthermore told American Cinematographer in 1997: "There will only be one. And it won't be what I would call the 'rought cut', it'll be the 'final cut.' The other one will be some sort of interesting artifact that people will look at and say, 'There was an earlier draft of this.'...What ends up being important in my mind is what the DVD version is going to look like, because that's what everybody is going to remember. The other versions will disappear. Even the 35 million tapes of Star Wars out there won't last more than 30 or 40 years. A hundred years from now, the only version of the movie that anyone will remember will be the DVD version [of the Special Edition]...I think it's the director's prerogative, not the studio's, to go back and reinvent a movie."

Lucas had just purchased the copyright to STAR WARS from Fox--most likely in exchange for letting them distribute the prequels--and now had true dictatorial control over the title. When the films were re-issued on VHS in 2000 the boxes had now removed the label of "Special Edition"--but not the content; and the film still claimed 1977 as its release date. Critics and audiences asked Lucas if the original would be released--for many, this was the film of their adolescence, and an edit of the movie deemed superior by just about everyone, aside from its historic value. But Lucas refused--for him, he felt that the original was now a half-complete embarrassment. Moreover, he hoped that the Special Edition would better integrate with the prequels he was releasing, so that the six film cycle could be seen as a more singular entity, and with all the criticism the prequels received, he was all the more stubborn and defensive that this happen in spite of what the rest of the world thought.

By 2001, VHS had been replaced by DVD and as landmarks like GONE WITH THE WIND, GODFATHER and ALIEN were released, many wondered why STAR WARS was mysteriously absent. Equally near-sighted was Lucas' plan to not release the films on DVD until after 2005. When DVD officially overtook VHS in sales in 2003, Lucas came to his senses--but the original version of STAR WARS was in more dire straits than ever. A second Special Edition was quickly put through--this time, plagued with so many audio glitches, color errors and timing issues that even the most ardently stubborn devotees of Lucas have a hard time appreciating this as a "Special Edition" (unless you think Darth Vader's pink lightsaber is a superior artistic choice).

This version added more prequel references, such as Jar Jar Binks and Hayden Christensen, replaced more many visual effects, and tossed aside the color palette of the original photography.

The original version, of course, was once again suppressed when the films arrived on DVD shelves in 2004. But Lucas went even further--embarking on a sort of crusade to eliminate the original from existence. Prints from the original version were recalled from circulation, and Lucasfilm only lent out 35mm prints of the Special Edition. There has been at least one documented instance where a theatre tried to screen a print sourced from collectors, as Lucasfilm refused, only to have official reps waiting to confiscate the print and shut down the screening. When American Cinemateque screened the film with a Q&A with model-maker Lorne Peterson as part of their tribute to ILM's pioneering FX in the mid-2000s, they were forced to screen a version of the film that only contained roughly 30% of that original groundbreaking work!

The Associated Press asked Lucas in 2004 why he didn't just release the original alongside the Special Edition, the way many movies had been done at that point. "The special edition, that's the one I wanted out there," Lucas replied. "The other movie, it's on VHS, if anybody wants it...to me, it doesn't really exist anymore. It's like this is the movie I wanted it to be, and I'm sorry you saw half a completed film and fell in love with it. But I want it to be the way I want it to be." Revealing a rather confused decision-making mindset that undoubtedly was influenced by the crushing criticism that 1999's PHANTOM MENACE and 2002's ATTACK OF THE CLONES received, Lucas defended his actions as: "I'm the one who has to take responsibility for it. I'm the one who has to have everybody throw rocks at me all the time, so at least if they're going to throw rocks at me, they're going to throw rocks at me for something I love rather than something I think is not very good, or at least something I think is not finished." Apparently unaware that no one ever would throw rocks at him for releasing the original versions of the films. In fact, many fans would take back anything bad they ever said about him!

By this time, fans were so outraged that they had actually formally organized themselves. Originaltrilogy.com was formed, offering a petition of signatures to Lucasfilm asking for the original versions of the trilogy to be released due their treasured status with fans and historical significance in the medium. By 2006, originaltrilogy.com's petition had astoundingly garnered over 70,000 signatures--a remarkable sign of how beloved the films were.

Due to this outcry, Lucasfilm VP Jim Ward begged Lucas to release the original versions. There finally was a small compromise--as a "bonus feature", a master tape of the transfer done in 1993 for Laserdisc was pulled out of a dust bin from the Lucasfilm archives and included as a bonus feature in a 2006 DVD re-release of the Special Edition, in non-anamorphic letterbox. This blatant disregard and disrespect for the film angered not just fans but film buffs around the world, naturally. After a massive letter-writing campaign, Lucasfilm finally responded to the criticism, saying that the 1993 tape represented the best source of the originals--obvious PR crap. Renowned film restorationist Robert Harris--the man who had hand-restored LAWRENCE OF ARABIA, SPARTACUS, THE SEARCHERS and GODFATHER--went on record saying he knew for a fact that there were pristine master 35mm elements available and that he would fully restore the original films! Lucasfilm did not respond to his offer.

Will the original STAR WARS ever be treated properly--at the very least, a modern transfer from 35mm elements? It's difficult to say right now. In the time since the 2006 "bonus feature" fiasco, Lucas' ego-maniacal theft of the films has become even more immature-looking--his friend Steven Spielberg restored all three versions of his CLOSE ENCOUNTERS, including his Director's Cut and the theatrical cut, his mentor Francis Coppola released both versions of APOCLAYPSE NOW in high quality, while three versions of George Romero's landmark DAWN OF THE DEAD are available in an attractive collection, and Ridley Scott's 2007 "Final Cut" of BLADE RUNNER was accompanied on video by full-out remastering of all four earlier versions, even a rare workprint copy. In a letter included in the collector's set, Scott writes: "I have included the four previously seen versions of the film in newly transferred anamorphic widescreen with original, unaltered 5.1 sound taken from the archival six tracks. My goal was to give you the film in whatever form you prefer, with the best picture and sound quality possible."

Lucas' refusal versus the demand of audiences has also sparked some debate about artistic merit and respect for the intentions of the artist. Indeed, it is not a comfortable answer to say that the artist should be forced to display a version of their work which they feel does not represent their wishes. However, most of this argument is based on revisionist fallacies. No filmmaker is ever totally satisfied with their finished work, which is part of the drive to work on a next one--Alfred Hitchcock is famous for having remarked when asked what his favorite film of his was: "the next one." The fact is that, regardless of whether Lucas likes it or not, STAR WARS was released as a finished product in 1977. It is 100% faithful to the shooting script, and on a technical level was the most advanced display of graphics ever made at that time. It was not "unfinished" in this sense, rather it simply was a product of the era that produced it.

Furthermore, the Special Edition has gone far beyond "completing" anything--his insertion of Jar Jar Binks and Hayden Christensen was obviously not in his mind when he made RETURN OF THE JEDI in 1983. Moreover, EMPIRE and JEDI were not even directed by him--while he is undoubtedly a primary creative force behind the franchise, these films are not "his" in this kind of direct sense. EMPIRE director Irvin Kershner, for example, maintained when he was hired in 1977 that he must be able to have artistic control over the production: "It'll be your film," Lucas told him. Lucas states to Rolling Stone on June 12, 1980: "It's truely Kershner's movie." Furthermore, JEDI director Richard Marquand has been dead for over twenty years [ed: Kershner is no longer with us either]. Lucas today represents a totally different person than the skinny 30-year old of 1977, and many of the changes are simply revisions, not completions.

But these are rather petty, technical arguments. The fact is that, if so many people enjoy the originals and would like to see them, wouldn't that please a filmmaker? One of the reasons no other director has refused to release a version of their film when there has been so much demand and love for it is precisely because of this. Ridley Scott hates the theatrical cut of BLADE RUNNER, and as one of the most powerful directors in the world he would have the ability to maintain it not be released--but many people either enjoy it or would like to see it simply for posterity, and that is not anything to be bothered by.

This brings me to the final, ultimately bottom-line, point. Lucas' preference and some sort of "auteur" argument is not even really what the issue is about; it's a strawman defense. No one ever has suggested that the Special Edition--Lucas' "Director's Version"--be suppressed, or replaced. That a filmmaker gets to re-shape their film the way they want is a great privilege that every director should enjoy, and no one should deny Lucas this. The issue is: releasing the original does not nullify the director's cut. Everyone would have treated the Special Edition as the final artistic statement of the director. They can both exist. In the current era of home video, there is no relevance in any argument that relies on only one version existing.

Much like how no one ignores the Final Cut of BLADE RUNNER just because the theatrical cut is on video, and no one feels that the director's cut of BRAZIL is nullified by the existence of the shortened "Love Conquer's All" version--when the films are sold, both cuts are included in the same package. When Orson Welles' TOUCH OF EVIL came out in a deluxe edition in 2008 it contained both the reconstructed director's cut that Welles had prepared as well as the important theatrical release. Historical posterity is important--it is important that students of film and audiences interested in history be able to see what films were like at the time they were actually made, and for audiences to continue to enjoy and watch them. Even if Leonardo DaVince's zombie corpse came back to life and wanted to repaint the Mona Lisa, the original culture-defining original work should not be blacked out of history, like some kind of Stalinist regime.

STAR WARS--and its two sequels--are important classics of cinema.

While the "Special Editions" are the same basic films, they do not in any way represent the look or experience of their original groundbreaking releases. This is an important issue in contemporary cinema, especially because, unlike any other films of historical significance that have not been restored (I actually can't think of any: DVD and Blu-ray have offered remarkable historic preservation of all the major classics), they are not being withheld due to neglect by the studio but due to a crusade of deliberate revisionism. And that is dangerous. In my opinion, this suppression of some of the cinema's classics represents one of the most heinous crimes against the medium, and one that people should take very seriously. Cinema is our cultural heritage, a reflection of our society, our technology and our values. As custodian of national treasures, there is an ethical mandate to preserve, protect, and display these works for the public good.

Lucas in the late 1980s spoke out against companies altering old films and colorizing black and white features; he claimed that, as a proponent of history, viewers should be able to appreciate a film as it was originally released. Nevermind any argument about artists versus companies altering films--Lucas is talking about history, and our shared heritage. "I am very concerned about our national heritage, and I am very concerned that the films that I watched when I was young and the films that I watched throughout my life are preserved, so that my children can see them," he said. He furthermore once remarked in 1988: "In the future it will become easier for old negatives to become lost and be 'replaced' by new altered negatives. This would be a great loss to our society. Our cultural history must not be allowed to be rewritten."

Perhaps he should re-examine his beliefs.